在场的:展开的真实

Presence: The Unfolding Reality

-

2021

摄影集 &随笔

Photography & Essays

“在場,看見,想像”

“事到如今,照片所給我們帶來的神秘性並沒有戛止。此前的歷史中沒有任何一個被講述的故事、沒有任何一種敘事可以帶有照片所存儲的那種:直白平庸的外觀下的「在場性」。這樣的外觀雖然沒有帶來附加的信息,但是它們卻是真切的存在本身。”

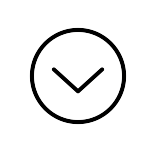

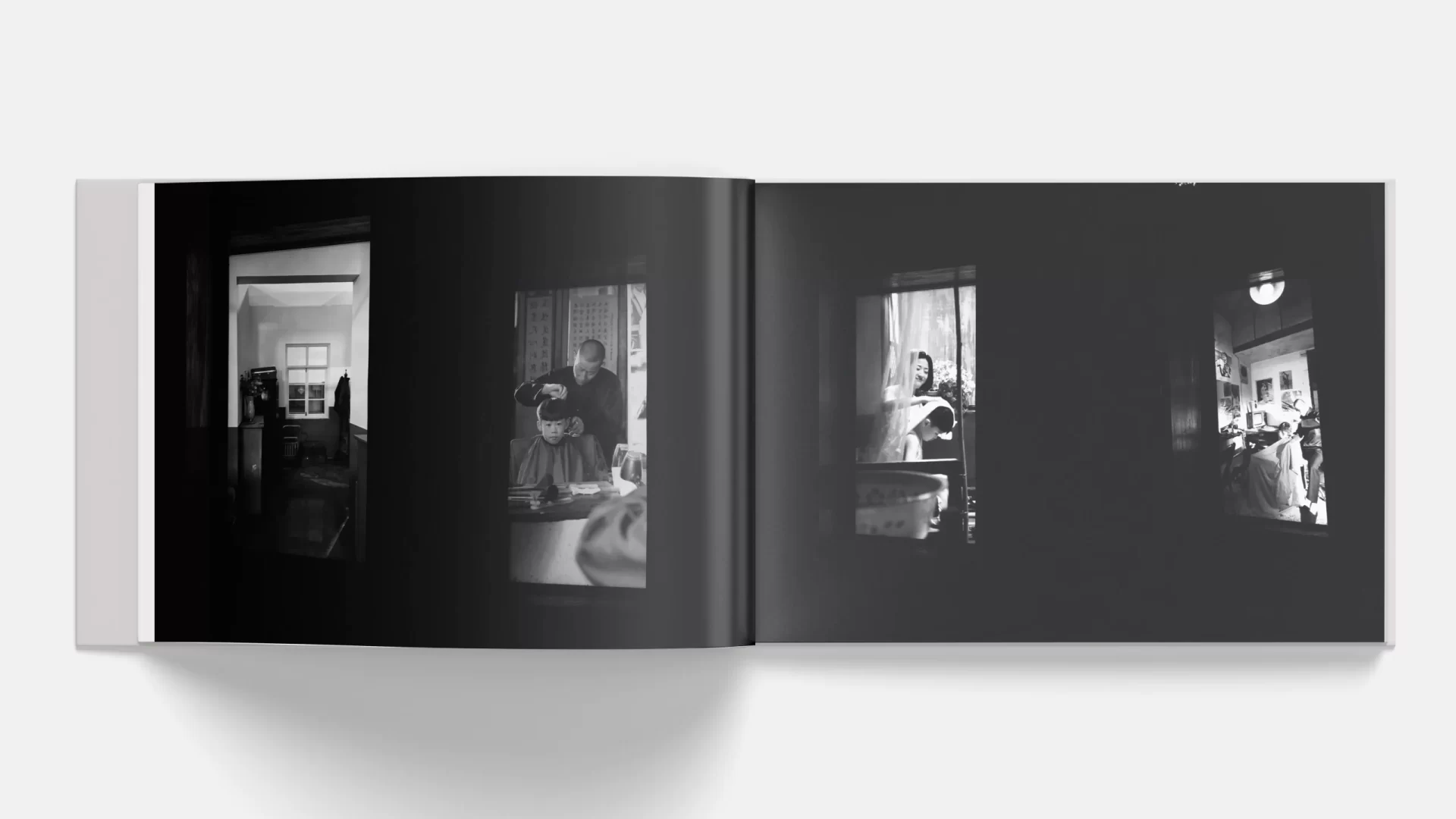

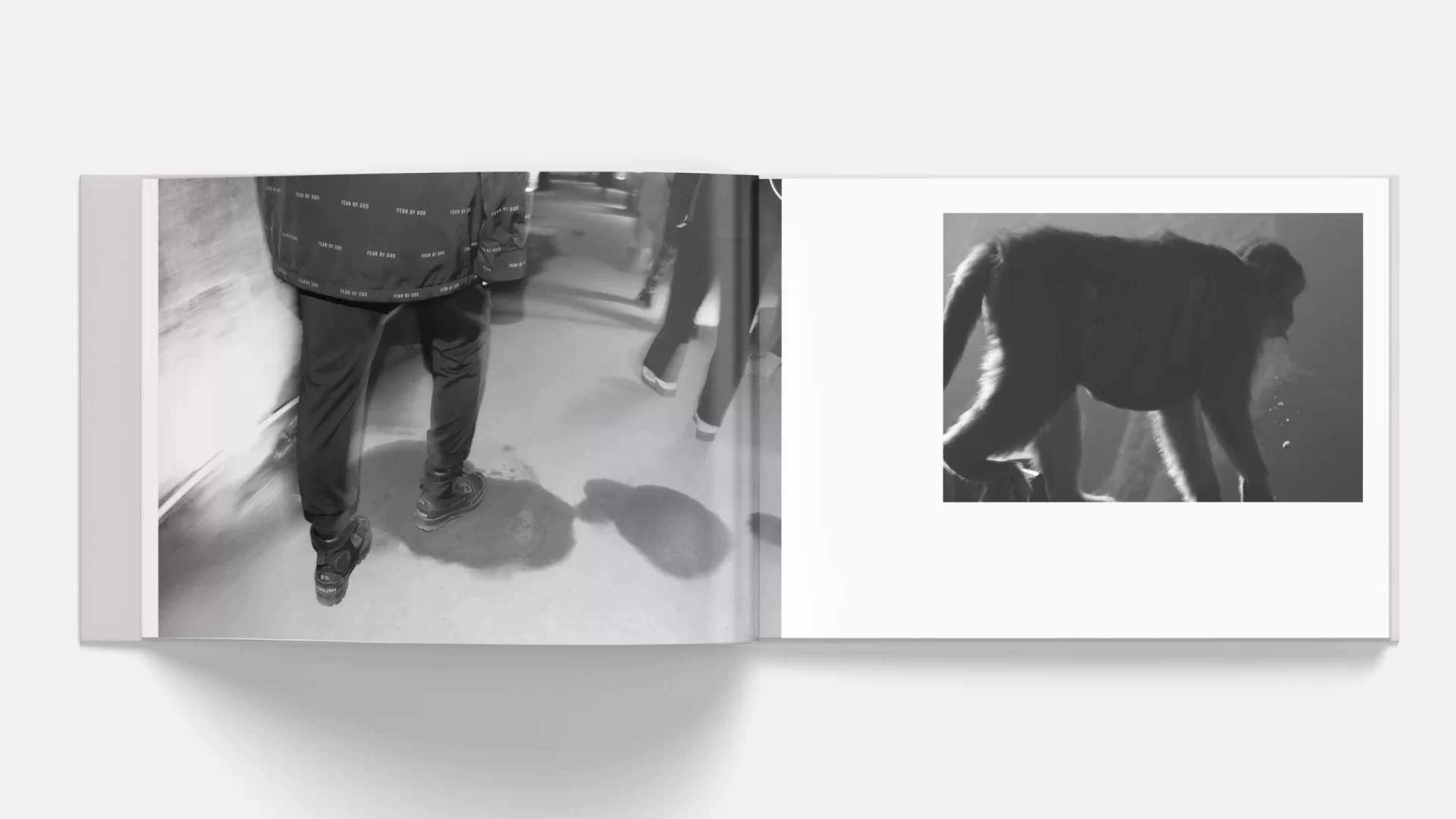

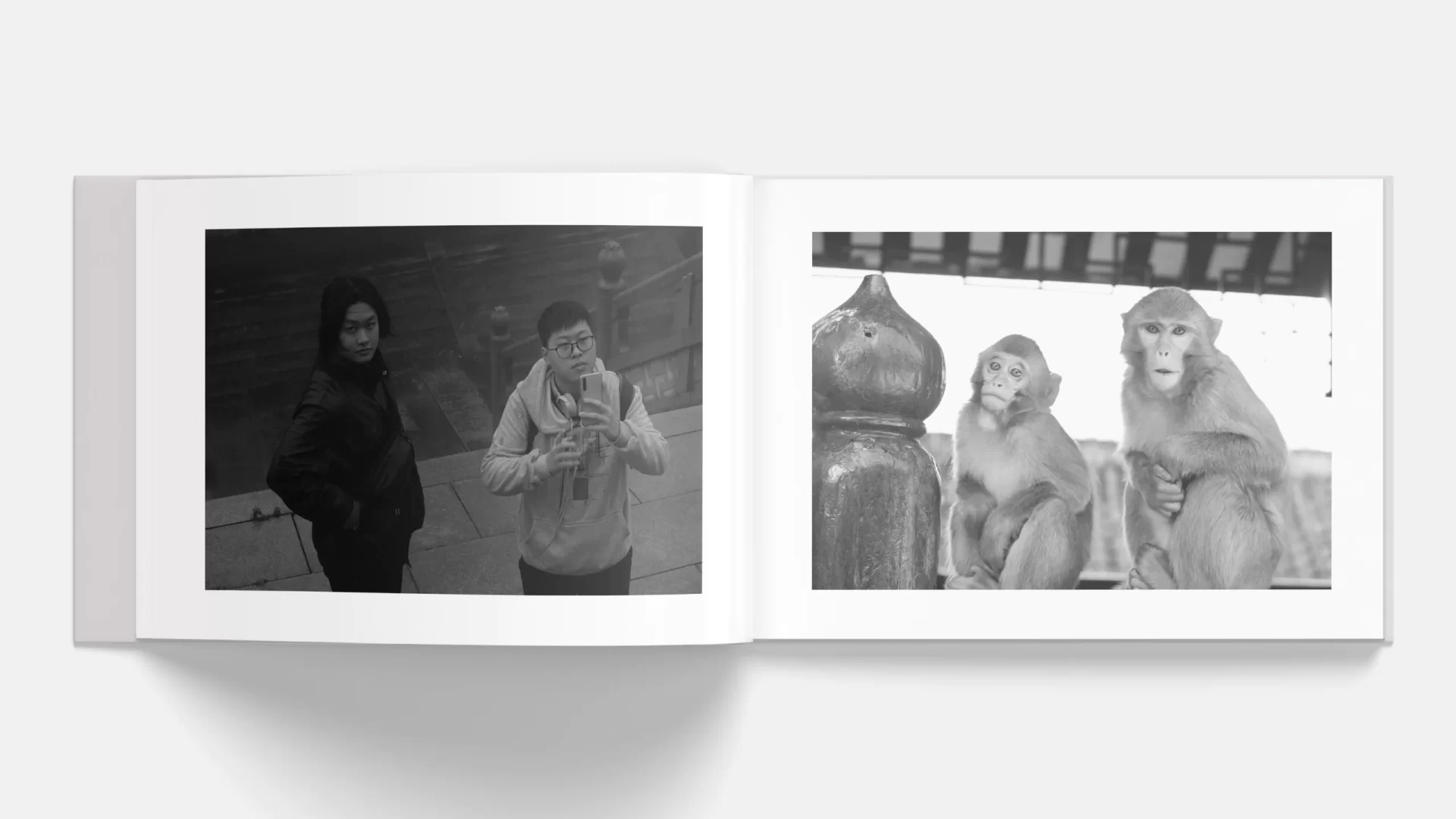

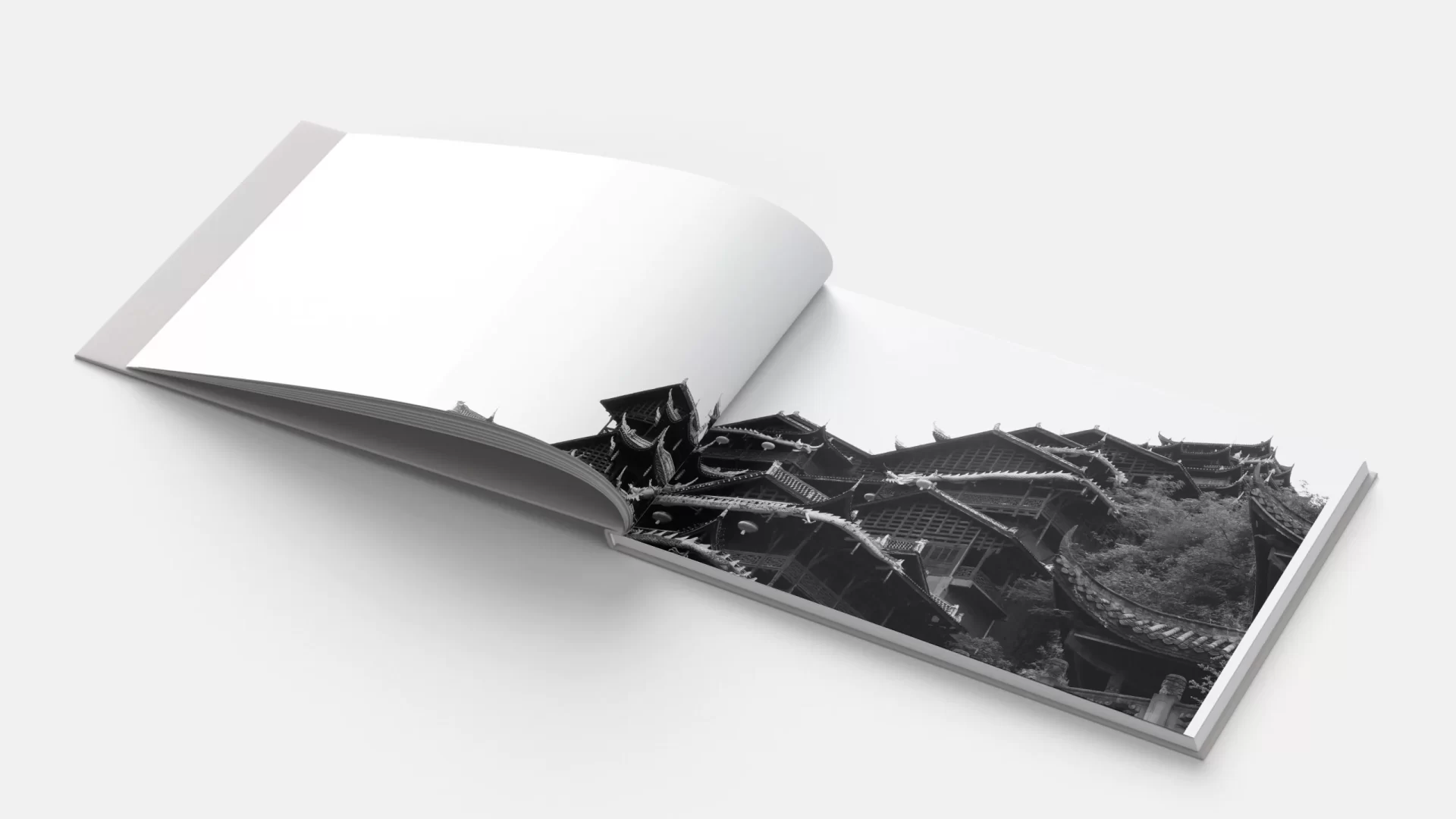

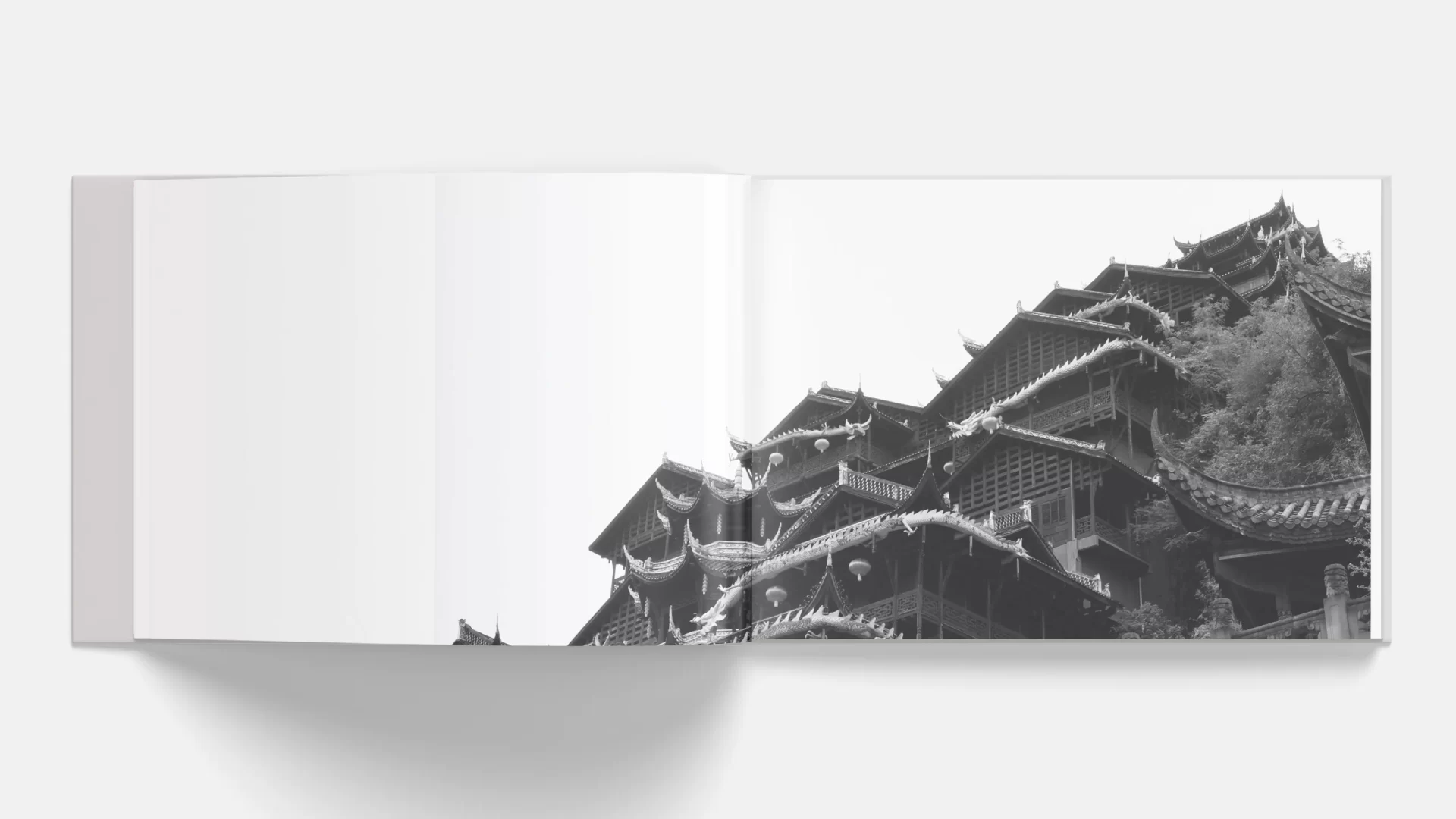

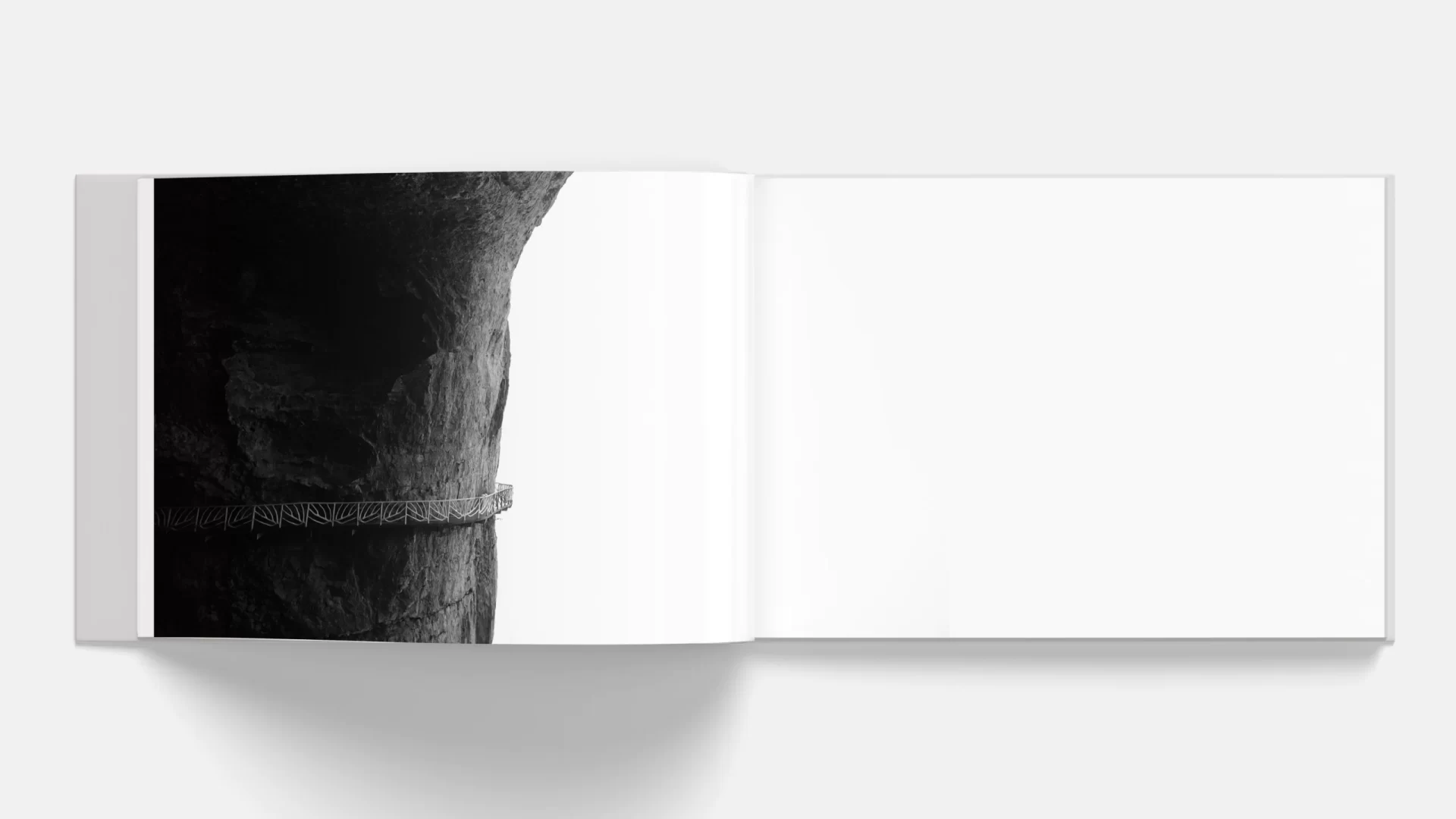

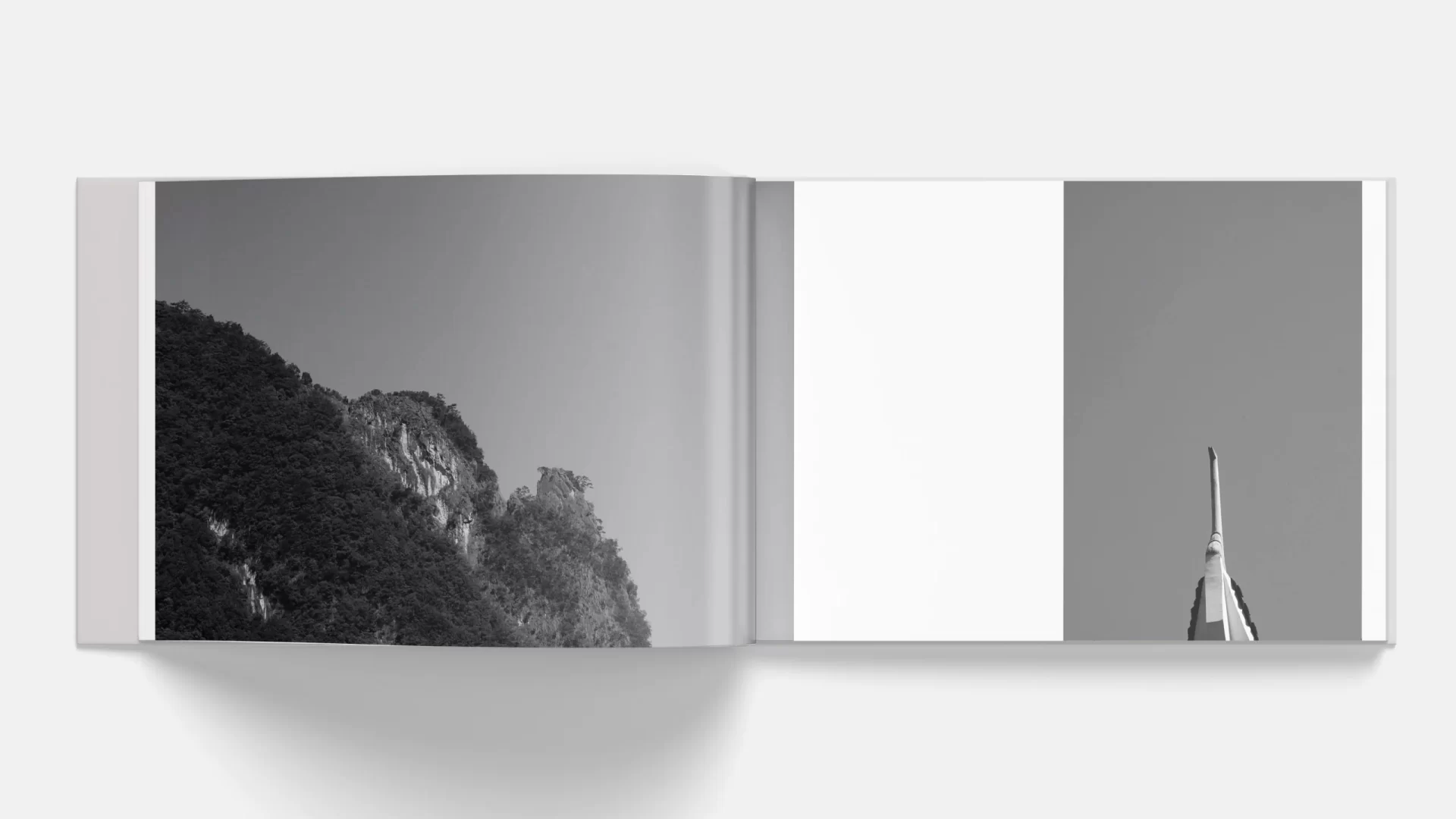

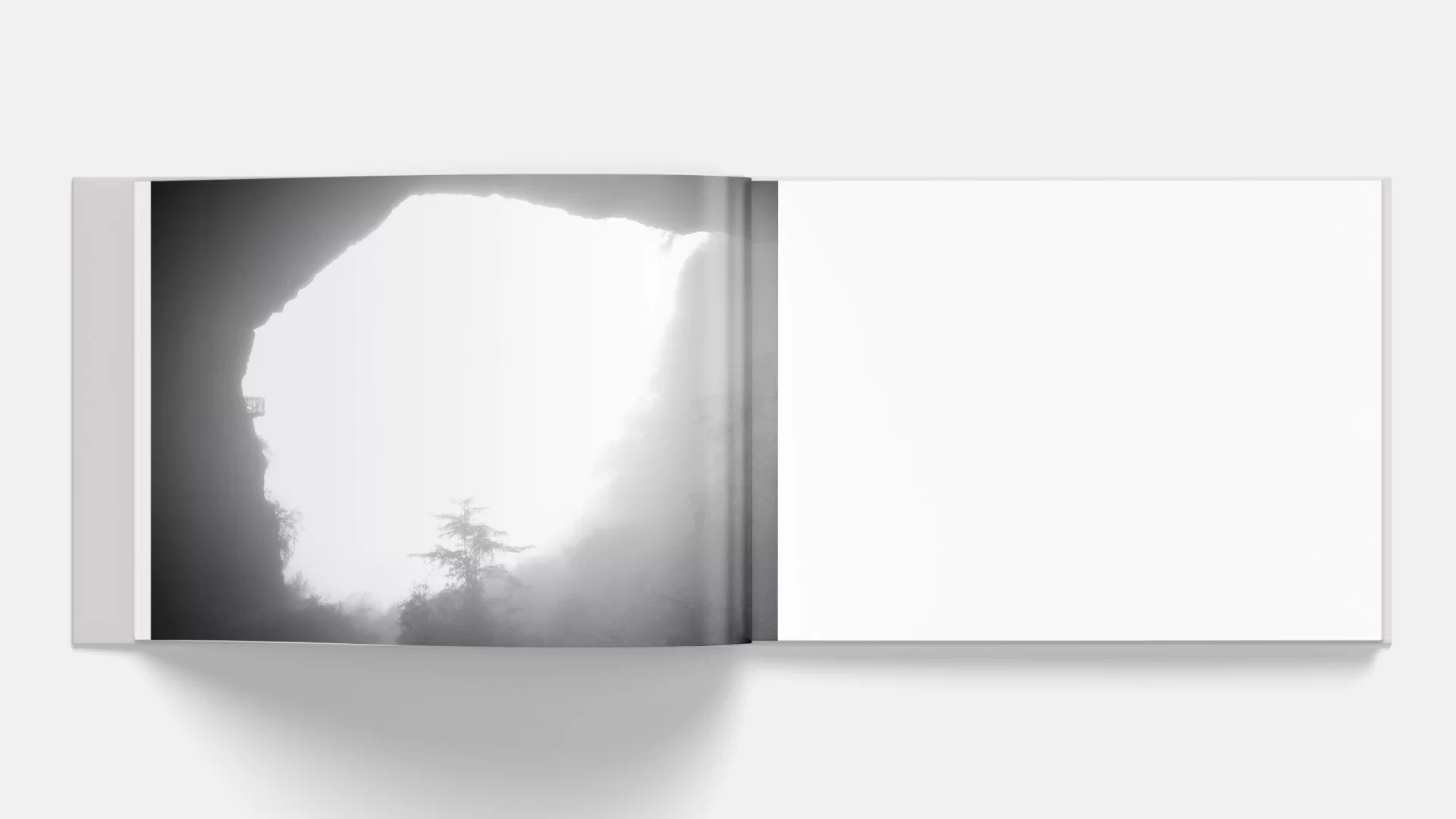

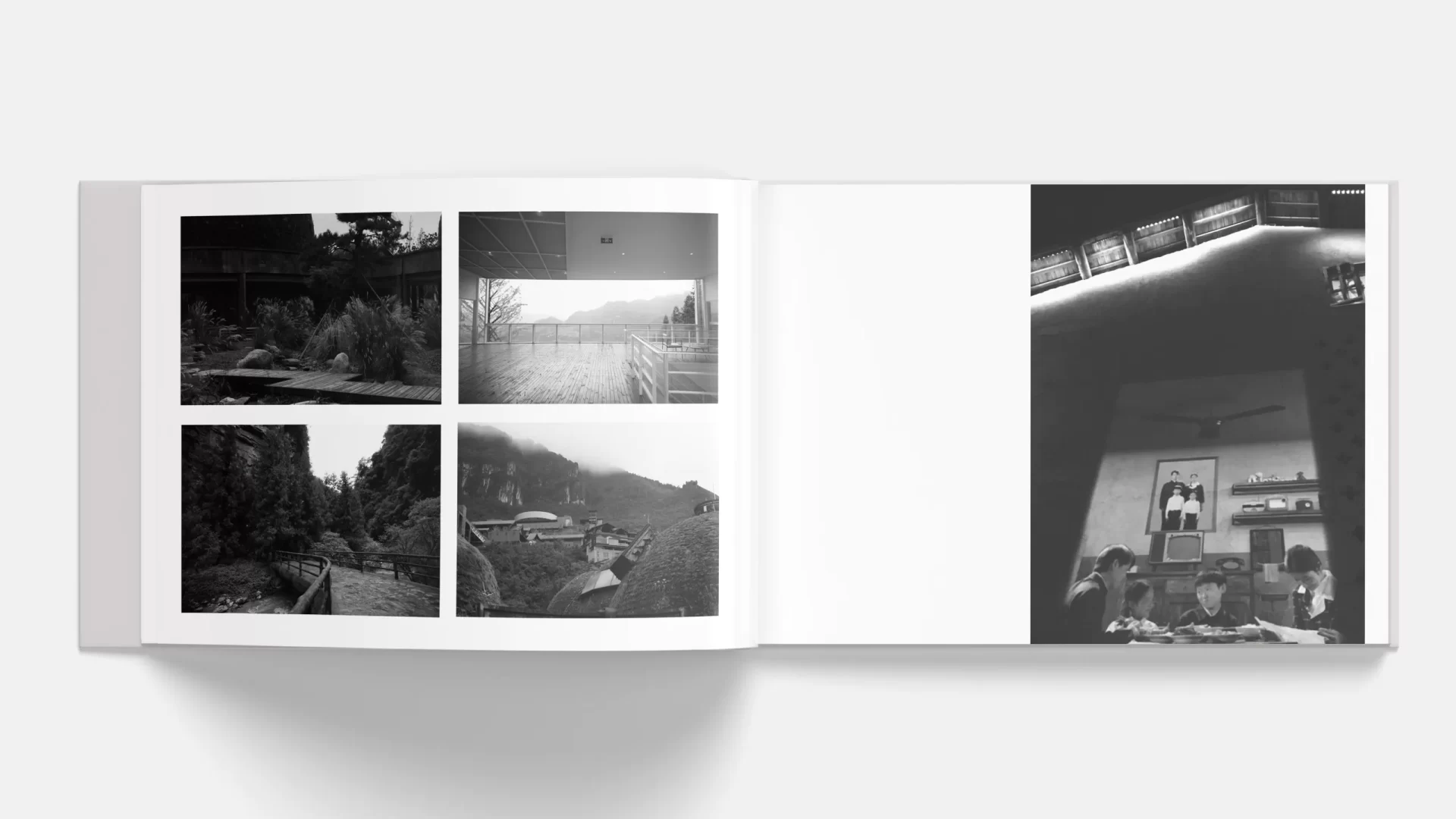

本次出行的10天時間裏,行列中的男男女女,路過的景致山川,一直在與我的眼睛發生交換,所以展示的是某種意義的現實。此集合是我途行之際的學習筆記及想象。在圖像泛濫的時代,攝影無疑提供了一種在場的確信感,從此,聲音、文本、圖形、動畫、靜態圖像及動態視頻文件等均可通過移動互聯網分享到世界各處。在這個意義上,同時,生產信息的個人得以借助攝影,人人有份的參與到時尚與現代的信息生活中。

“Presence · Witnessing · Imagining”

“To this day, the mystery that photographs bring us has not ceased. In the history that precedes us, no story that has been told, no narrative, possesses the kind of ‘presence’ stored in photographs: an appearance that is straightforward and mundane. Such appearances, although they do not convey additional information, represent a genuine existence itself.”

During the 10 days of this trip, the men and women in the group, the passing landscapes and mountains, have been exchanging with my eyes, hence presenting a certain reality of meaning. This collection is my learning notes and imagination during the journey. In an era flooded with images, photography undoubtedly provides a sense of presence on the spot. From now on, sounds, texts, graphics, animations, static images, and moving video files can all be shared across the globe via the mobile internet. In this sense, individuals producing information can, through photography, participate in the fashionable and modern information life that is accessible to everyone.

“在場,看見,想像”

“事到如今,照片所給我們帶來的神秘性並沒有戛止。此前的歷史中沒有任何一個被講述的故事、沒有任何一種敘事可以帶有照片所存儲的那種:直白平庸的外觀下的「在場性」。這樣的外觀雖然沒有帶來附加的信息,但是它們卻是真切的存在本身。”

本次出行的10天時間裏,行列中的男男女女,路過的景致山川,一直在與我的眼睛發生交換,所以展示的是某種意義的現實。此集合是我途行之際的學習筆記及想象。在圖像泛濫的時代,攝影無疑提供了一種在場的確信感,從此,聲音、文本、圖形、動畫、靜態圖像及動態視頻文件等均可通過移動互聯網分享到世界各處。在這個意義上,同時,生產信息的個人得以借助攝影,人人有份的參與到時尚與現代的信息生活中。

“Presence · Witnessing · Imagining”

“To this day, the mystery that photographs bring us has not ceased. In the history that precedes us, no story that has been told, no narrative, possesses the kind of ‘presence’ stored in photographs: an appearance that is straightforward and mundane. Such appearances, although they do not convey additional information, represent a genuine existence itself.”

During the 10 days of this trip, the men and women in the group, the passing landscapes and mountains, have been exchanging with my eyes, hence presenting a certain reality of meaning. This collection is my learning notes and imagination during the journey. In an era flooded with images, photography undoubtedly provides a sense of presence on the spot. From now on, sounds, texts, graphics, animations, static images, and moving video files can all be shared across the globe via the mobile internet. In this sense, individuals producing information can, through photography, participate in the fashionable and modern information life that is accessible to everyone.

我们都喜爱摄影吧

攝影之所以能夠成為奇妙的發明,因為它總是擁有難以預料。當然在數碼時代來臨之後,攝影師「難以預料」的感官時長從沖洗膠片再放大成片,無限縮短為數碼相機內部的COMS感光成像圖像數據傳輸到數碼屏中的毫秒以計。於是攝影最珍貴的原材料:光和時間便成為了光圈快門的設置:一系列規整工業流程式的曝光參數。

在我們感興趣的攝影過程中,觀看照片的人以及掌握快門的攝影師總喜歡做一個發明意義的遊戲。

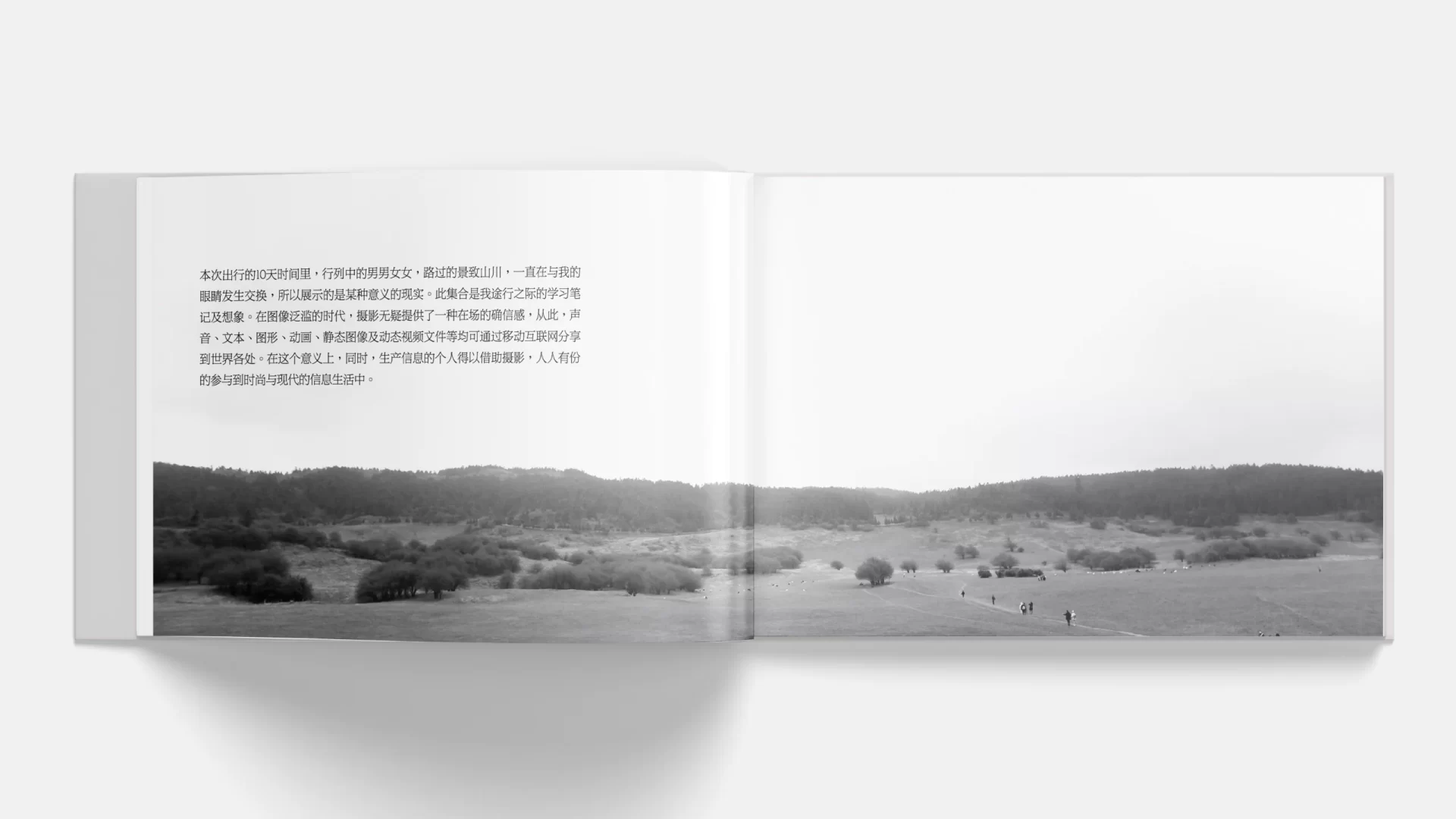

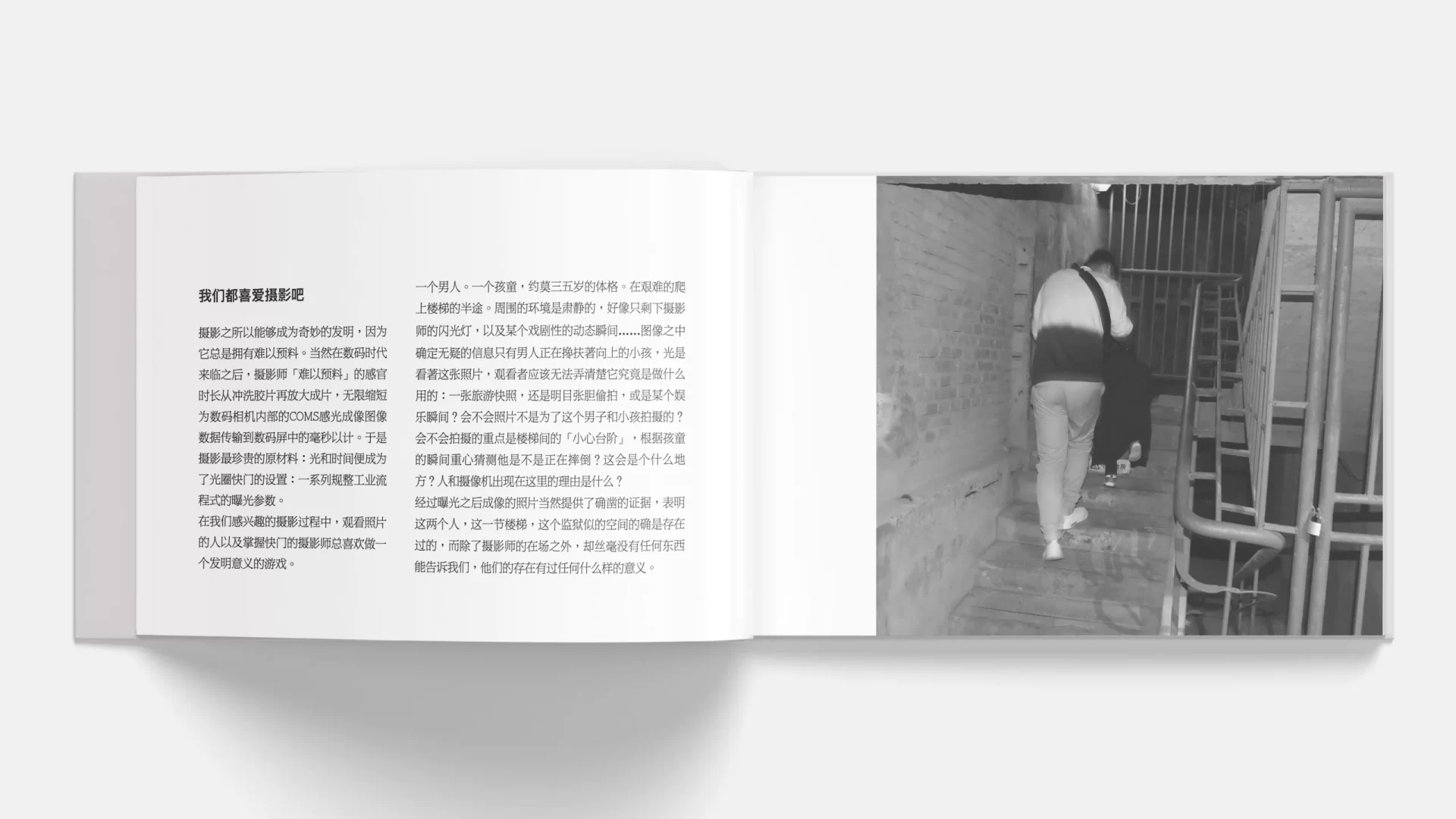

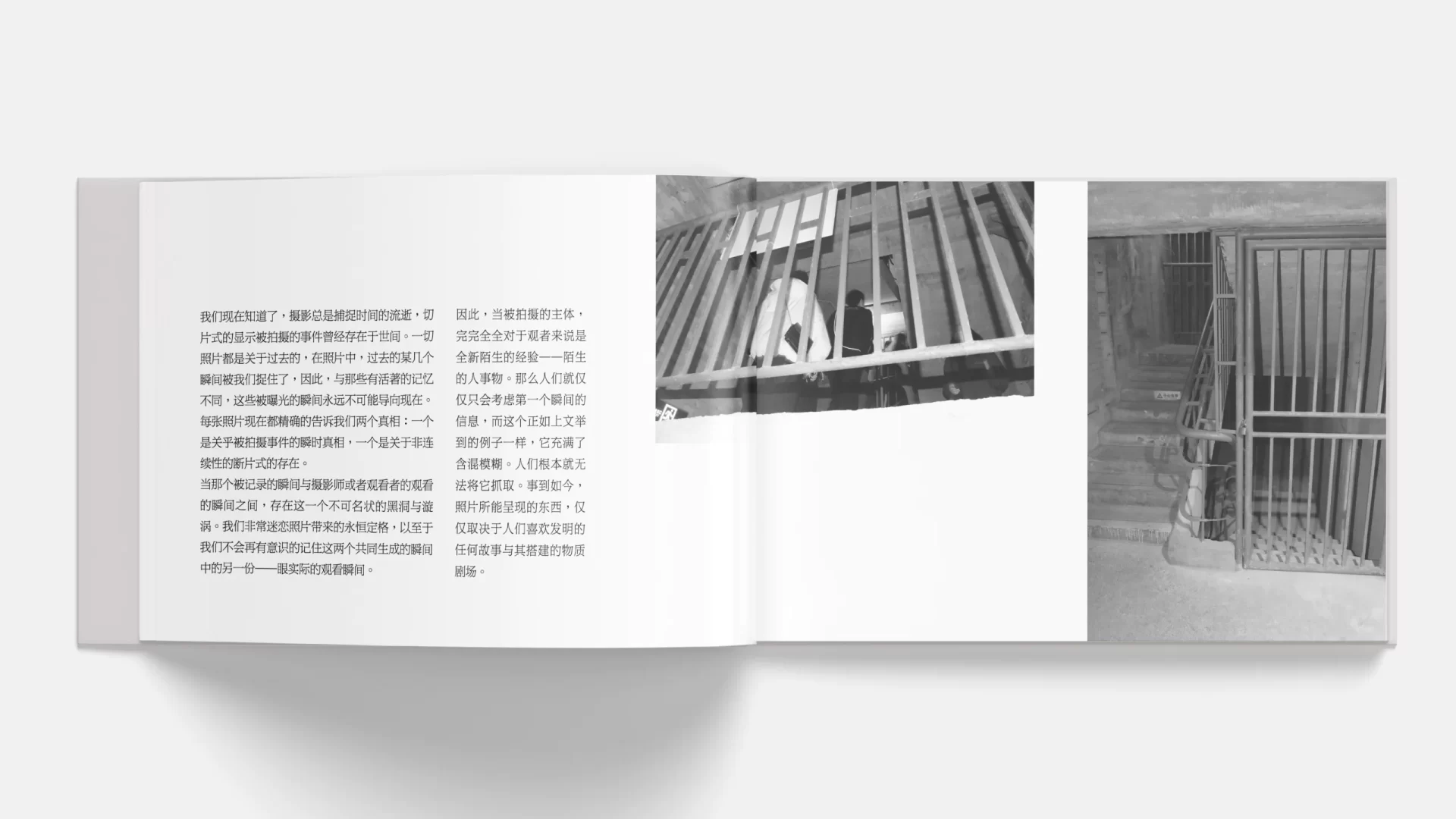

在这张照片中,一個男人。一個孩童,約莫三五歲的體格。在艱難的爬上樓梯的半途。周圍的環境是肅靜的,好像只剩下攝影師的閃光燈,以及某個戲劇性的動態瞬間……圖像之中確定無疑的信息只有男人正在攙扶著向上的小孩,光是看著這張照片,觀看者應該無法弄清楚它究竟是做什麼用的:一張旅遊快照,還是明目張膽偷拍,或是某個娛樂瞬間?會不會照片不是為了這個男子和小孩拍攝的?會不會拍攝的重點是樓梯間的「小心台階」,根據孩童的瞬間重心猜測他是不是正在摔倒?這會是個什麼地方?人和攝像機出現在這裡的理由是什麼?

經過曝光之後成像的照片當然提供了確鑿的證據,表明這兩個人,這一節樓梯,這個監獄似的空間的確是存在過的,而除了攝影師的在場之外,卻絲毫沒有任何東西能告訴我們,他們的存在有過任何什麼樣的意義

The Wonders of Photography

Photography has become a remarkable invention because it always harbors the unpredictable. Certainly, with the advent of the digital age, the ‘unpredictable’ duration a photographer experiences has drastically shortened from the time it takes to develop film and enlarge prints to mere milliseconds it takes for the CMOS sensor inside a digital camera to transmit image data to a digital screen. Thus, photography’s most precious raw materials: light and time, have become settings of aperture and shutter speed: a series of regimented, industrial process-like exposure parameters.

In the photography process that interests us, both the viewers of the photographs and the photographers holding the shutter always seem to enjoy playing a game of inventive significance.

In this photo, a man. A child, roughly three to five years old in stature, is halfway through a difficult climb up the stairs. The surrounding environment is quiet, as if only the photographer’s flash and a certain dramatic moment in motion remain… The only definitive information within the image is the man assisting the child upwards. Just by looking at this photo, the viewer might not be able to ascertain its purpose: is it a travel snapshot, a brazen act of voyeurism, or a moment of entertainment? Could it be that the photo wasn’t taken for the man and child at all? Could the focus of the shot be the “watch your step” sign on the stairway, guessing from the child’s momentary center of gravity whether he is falling? What place could this be? What reason do people and the camera have to be there?

The photo, once exposed and developed, indeed provides irrefutable evidence that these two individuals, this segment of the staircase, and this prison-like space did exist. However, apart from the presence of the photographer, nothing else can tell us if their existence held any kind of significance

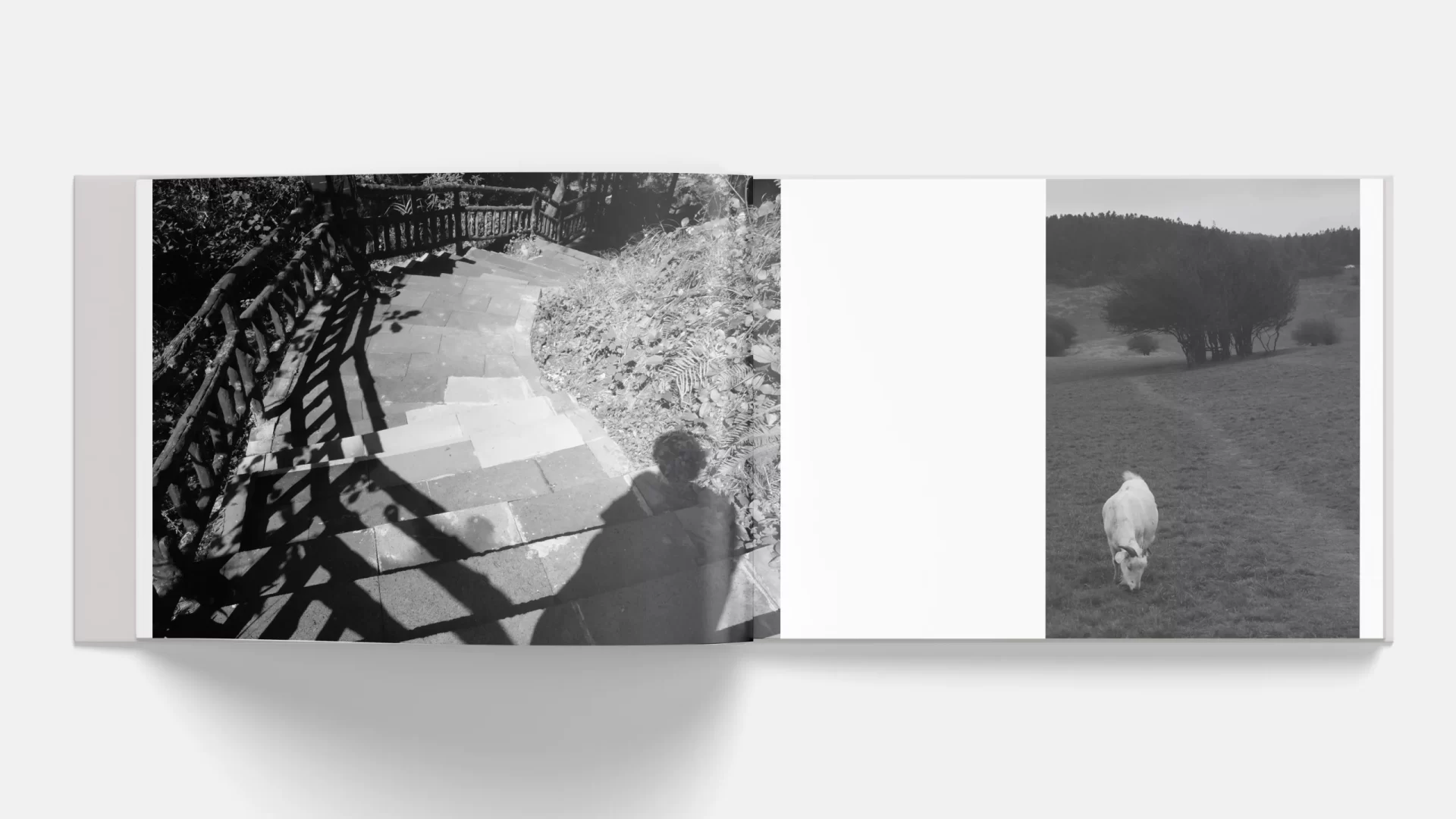

我們現在知道了,攝影總是捕捉時間的流逝,切片式的顯示被拍攝的事件曾經存在於世間。一切照片都是關於過去的,在照片中,過去的某幾個瞬間被我們捉住了,因此,與那些有活著的記憶不同,這些被曝光的瞬間永遠不可能導向現在。每張照片現在都精確的告訴我們兩個真相:一個是關乎被拍攝事件的瞬時真相,一個是關於非連續性的斷片式的存在。

當那個被記錄的瞬間與攝影師或者觀看者的觀看的瞬間之間,存在這一個不可名狀的黑洞與漩渦。我們非常迷戀照片帶來的永恆定格,以至於我們不會再有意識的記住這兩個共同生成的瞬間中的另一份——眼實際的觀看瞬間。

因此,當被拍攝的主體,完完全全對於觀者來說是全新陌生的經驗——陌生的人事物。那麼人們就僅僅只會考慮第一個瞬間的信息,而這個正如上文舉到的例子一樣,它充滿了含混模糊。人們根本就無法將它抓取。事到如今,照片所能呈現的東西,僅僅取決於人們喜歡發明的任何故事與其搭建的物質劇場。

We now understand that photography always captures the passage of time, slicing moments to display that the events photographed once existed in this world. Every photo is about the past; in photographs, certain moments of the past are seized by us, and thus, unlike those memories that are alive, these exposed moments can never lead to the present. Each photo now precisely tells us two truths: one is about the instantaneous truth of the photographed event, and the other is about a discontinuous, fragmented existence.

Between the moment captured and the moment it is observed by the photographer or viewer, there exists an indescribable black hole and vortex. We are so fascinated by the eternal freeze-frame that photos offer that we no longer consciously remember the other moment produced in tandem—the actual moment of seeing with our eyes.

Therefore, when the subject photographed is completely new and foreign to the viewer—an unfamiliar person, event, or thing—people tend only to consider the information from the first moment, which, as previously mentioned, is filled with ambiguity and blurriness. People simply cannot grasp it. At this point, what a photo can present is merely dependent on any story people like to invent and the material theater they build.

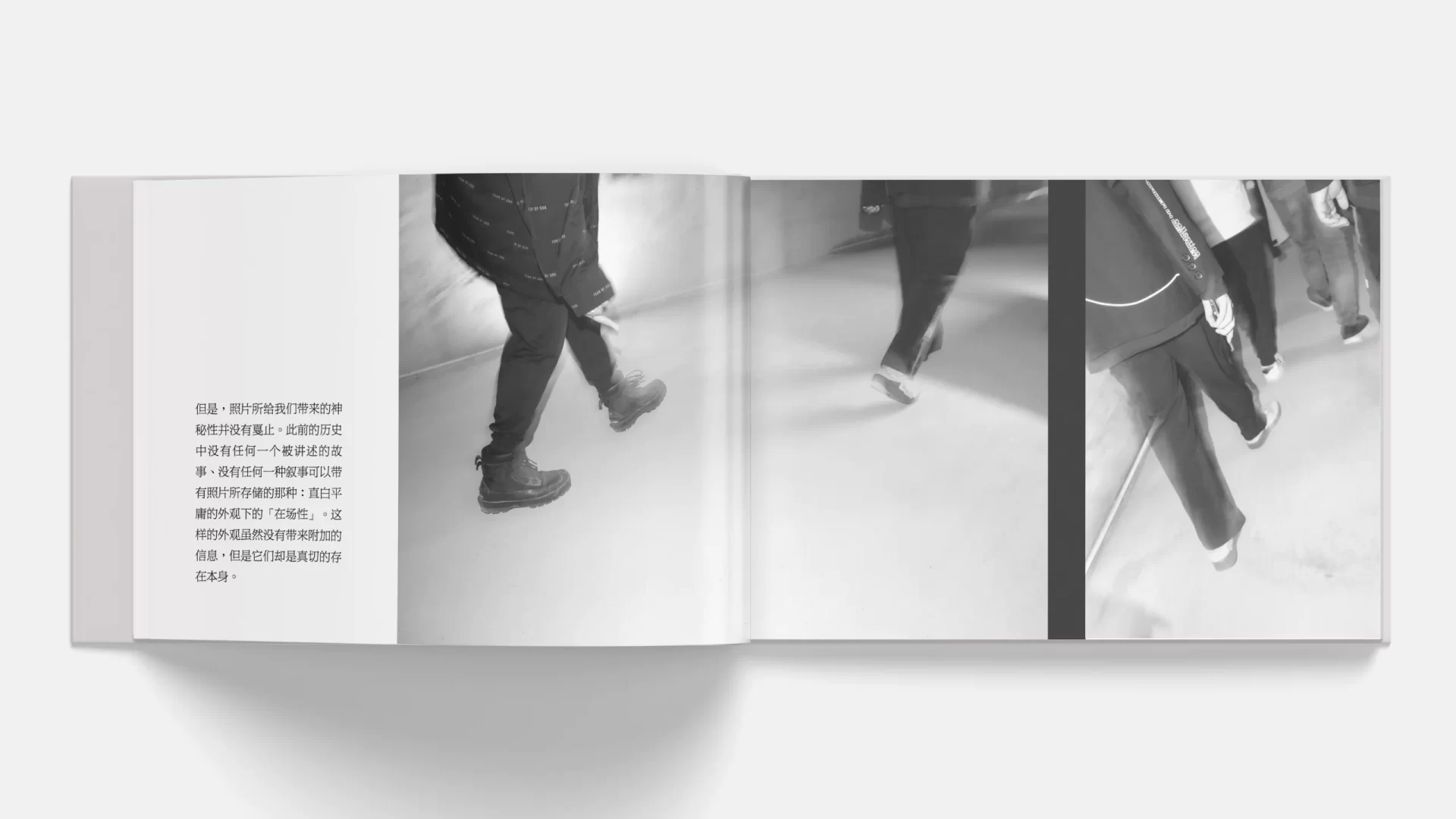

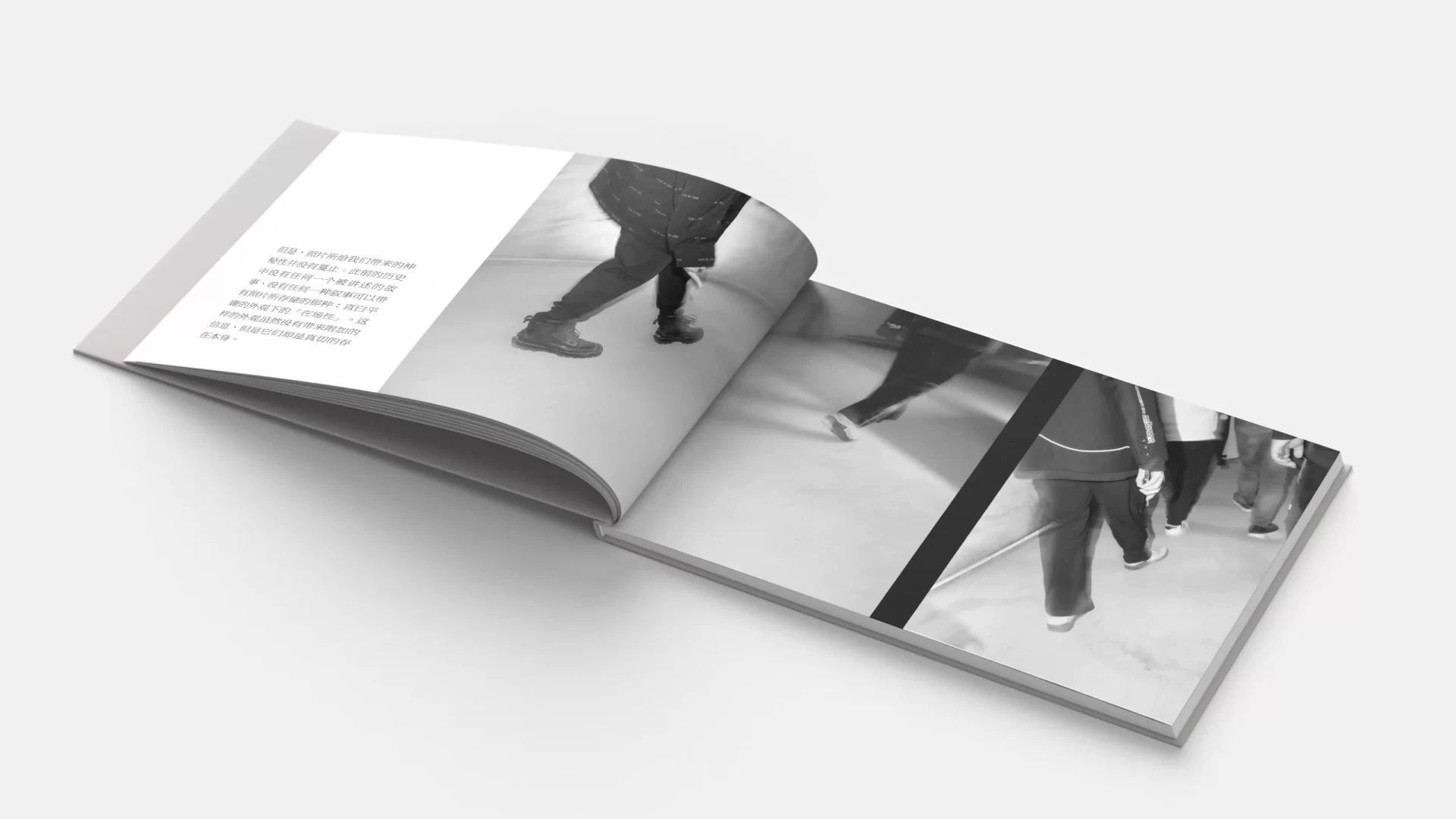

但是,照片所給我們帶來的神秘性並沒有戛止。此前的歷史中沒有任何一個被講述的故事、沒有任何一種敘事可以帶有照片所存儲的那種:直白平庸的外觀下的「在場性」。這樣的外觀雖然沒有帶來附加的信息,但是它們卻是真切的存在本身。

However, the mystique that photographs bring to us has not ceased. In the history that preceded us, no recounted story, no form of narrative could possess what a photograph stores: the “presence” beneath its straightforward and ordinary appearance. Although such appearances do not convey additional information, they are indeed the essence of existence itself.

所以真相大白了

所以照片會保存時間的一個瞬間,阻止它被後來的瞬間抹去。基於此,照片或許可以和存儲在人腦海中的記憶的圖像相比較,但其中的根本性差距就如上所提:記憶中的圖像是長續經驗的剩餘切片,而照片卻將毫不相關的瞬間的外觀獨立。

在人類的經驗中,意義並不是憑空出現的,它存在於事與事的上下聯繫中,如果沒有事物的連續運動,那麼意義就無法生成——沒有敘事,沒有展開,便沒有意義。所以,當我們通過方法賦予事件意義時,那麼此刻的意義便承接了上下經歷的反應和結論——也就是說,當我們發現一張照片有意義時,那是因為我們賦予了它過去和未來。

在社會文明的發展過程中,圖像和文字共同推動著文明的進步。在圖像爆炸的時代來臨之前,人類對山川河海以及人造景觀的理解與思考是小眾化的。隨著圖像的爆炸,流媒體平台等的出現,使圖像的大面積傳播成為可能,消費主義語境下視覺文化的興起,不斷衝擊以語言文字傳播為中心的傳統信息交互模式。無論是風光攝影還是紀實攝影,都不只是藝術的表達,更是真實的記錄,大部分情況下再現真實是攝影的原則。格倫伯格指出,「攝影是視覺藝術中最透明的媒介,它以令人信服的視角和無縫的細節再現事物」。

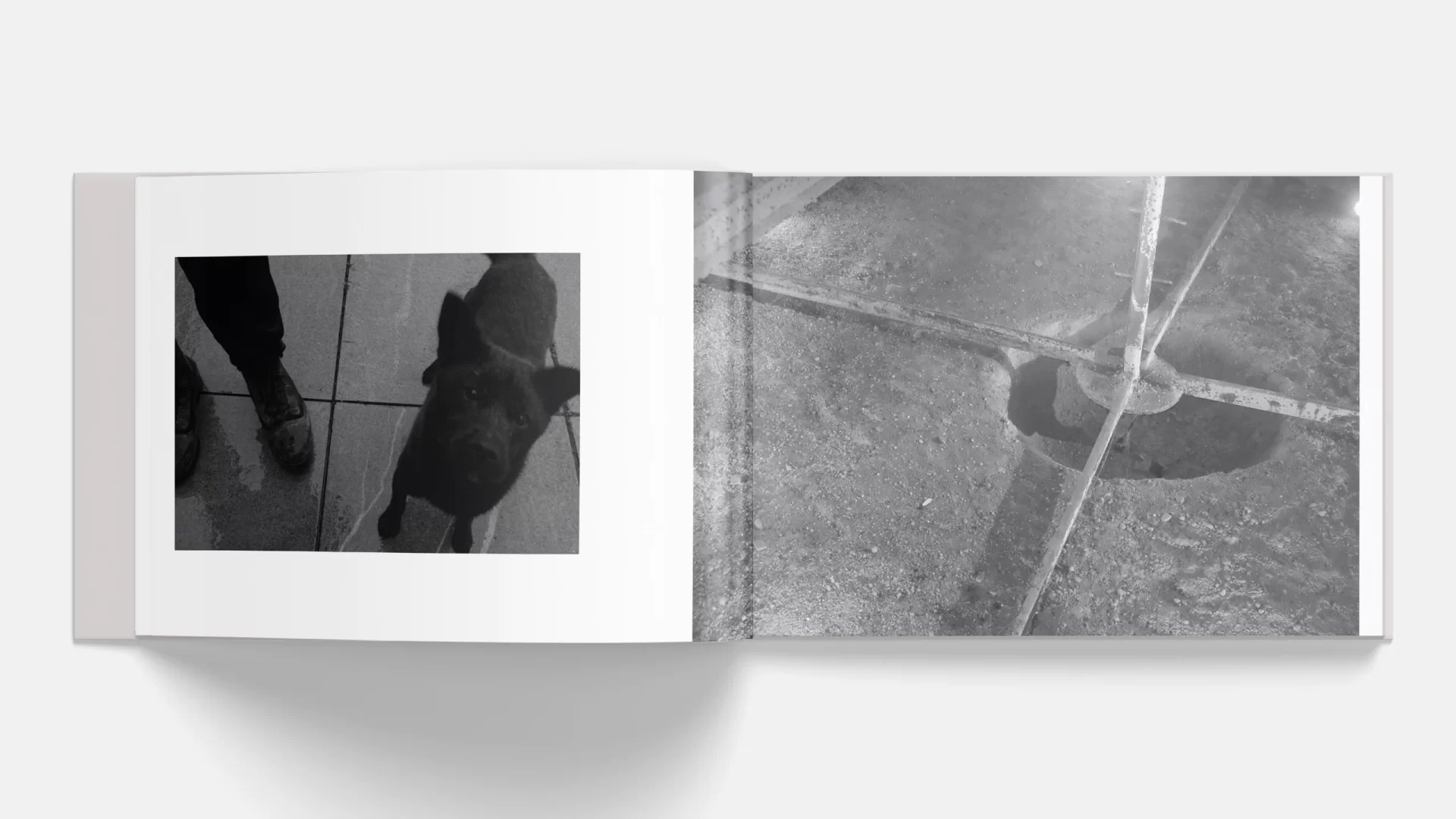

當下無論我們是拿起手機還是蓄謀已久的照相機,它們都有一個共同特點,即我們是主動介入攝影的。我們將要攝影主要是受到被攝物對我們的某種「刺激」所致,這些場景往往也是可遇不可求的。街頭有趣的時刻、行程中無意的一瞥乃至日常生活中的突發事件等等,它們也有一個共同特點,即此刻我們是被動介入攝影的。上述場景在以往大都停留在當事者的記憶中。

The Truth Unveiled

So, a photograph preserves a moment in time, preventing it from being erased by subsequent moments. Based on this, photographs can perhaps be compared to images stored in human memory, but the fundamental difference is as mentioned before: images in memory are remnants of continuous experience, whereas a photograph isolates the appearance of unrelated moments.

In human experience, meaning does not arise out of nothing; it exists in the context of the connection between things. If there is no continuous motion of things, then meaning cannot be generated—without narrative, without development, there is no meaning. Therefore, when we attribute meaning to events through methods, the significance at that moment carries the reaction and conclusion of the past and future experiences—that is to say, when we find a photograph meaningful, it is because we have attributed to it a past and a future.

In the development process of human civilization, images and texts have jointly propelled the progress of civilization. Before the era of the image explosion, the understanding and contemplation of mountains, rivers, seas, and human-made landscapes were niche. With the explosion of images and the emergence of streaming platforms, the widespread dissemination of images has become possible, and the rise of visual culture under the context of consumerism continuously impacts the traditional information interaction model centered on language and text communication. Whether it is landscape photography or documentary photography, it is not only an artistic expression but also a real record; in most cases, representing reality is the principle of photography. Glunberg pointed out, “Photography is the most transparent medium in visual arts, it reproduces objects with convincing perspectives and seamless details.”

Now, whether we pick up a mobile phone or a premeditated camera, they share a common characteristic: we are actively intervening in photography. The primary reason we engage in photography is due to some “stimulation” from the subject, and these scenes are often serendipitous. Interesting moments on the street, an unintentional glance during a journey, or sudden events in daily life, etc., share another common characteristic: at these moments, we are passively involved in photography. The aforementioned scenarios mostly remain in the memory of the participants.

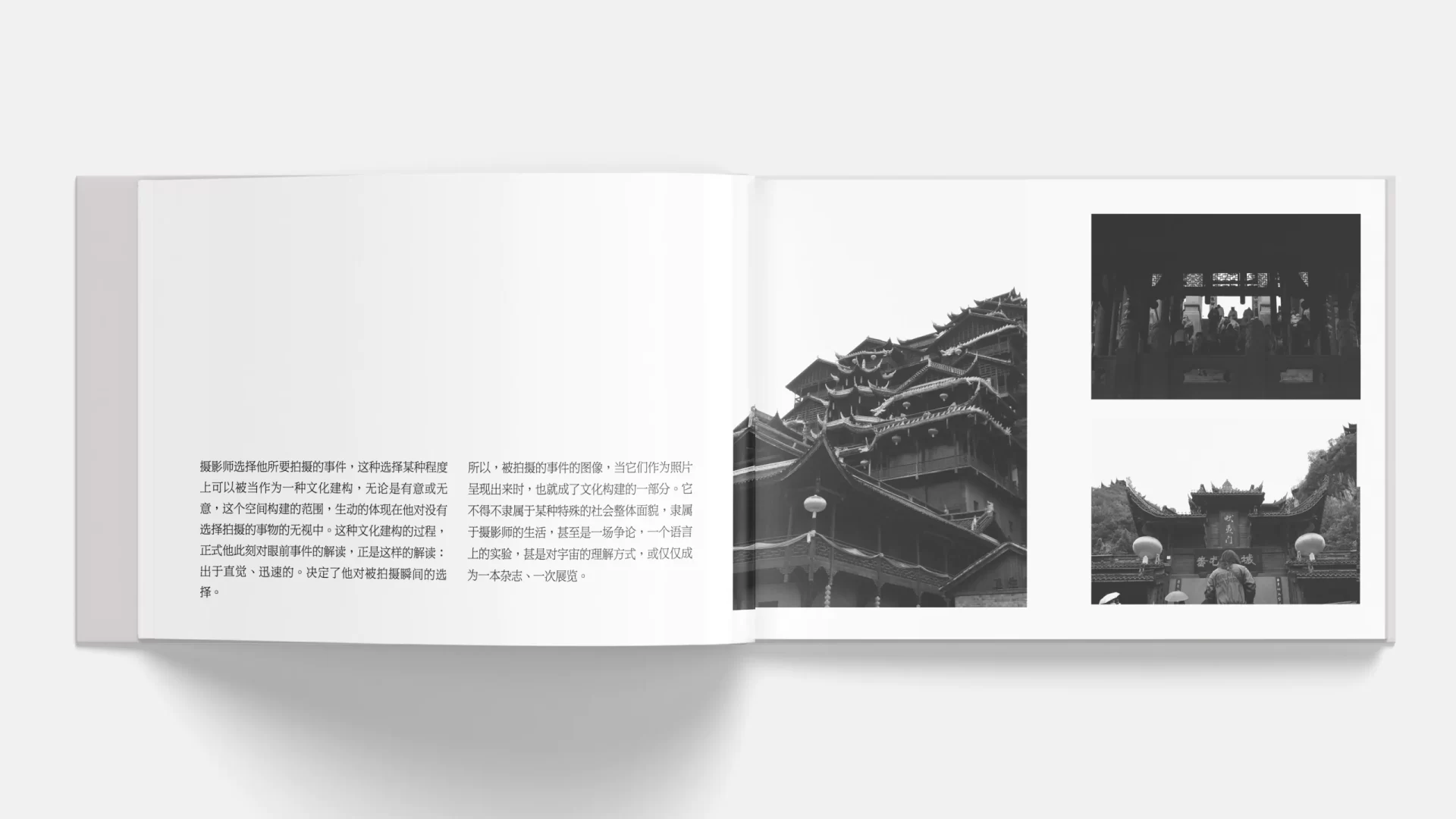

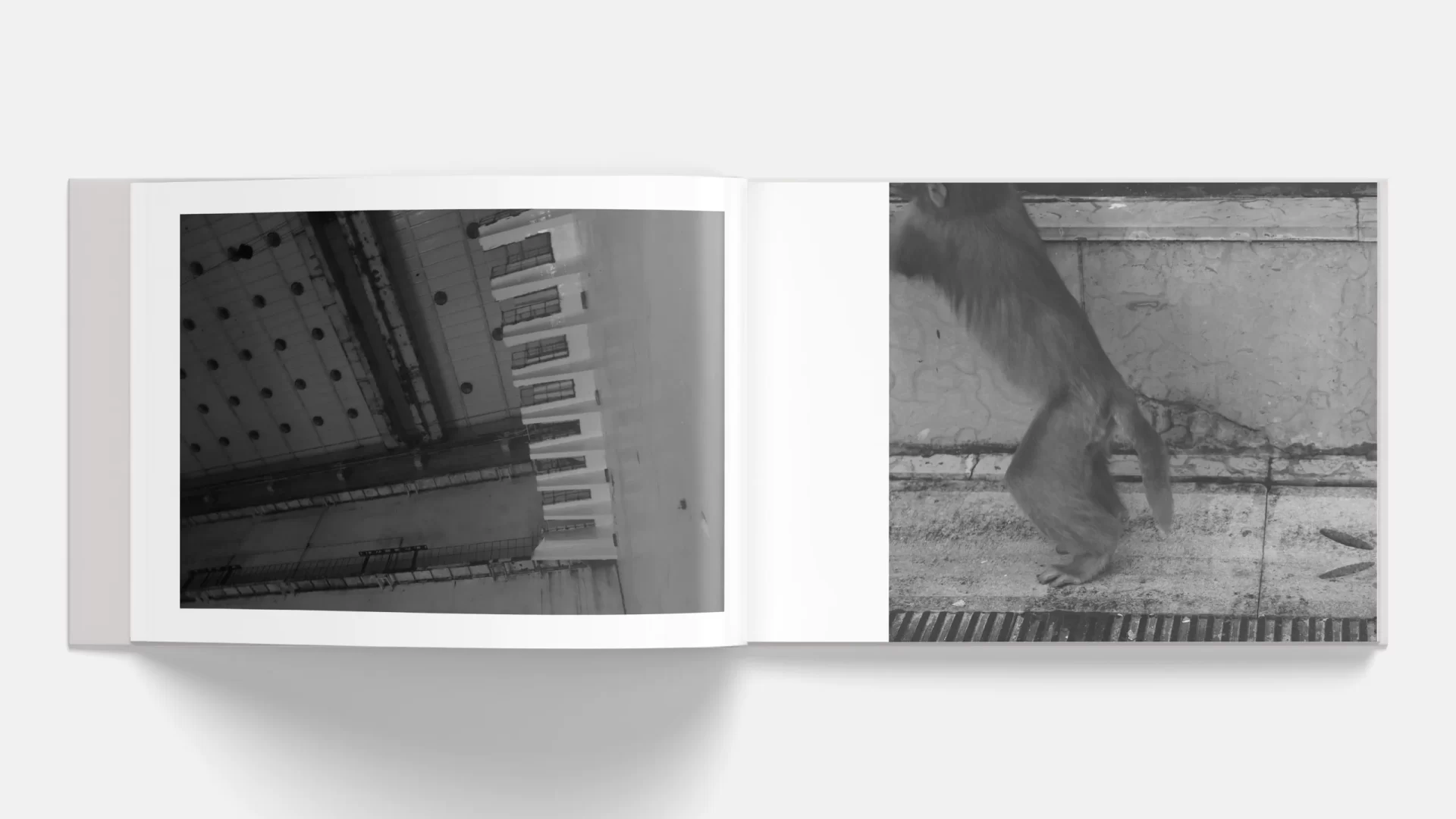

攝影師選擇他所要拍攝的事件,這種選擇某種程度上可以被當作為一種文化建構,無論是有意或無意,這個空間構建的範圍,生動的體現在他對沒有選擇拍攝的事物的無視中。這種文化建構的過程,正式他此刻對眼前事件的解讀,正是這樣的解讀:出於直覺、迅速的。決定了他對被拍攝瞬間的選擇。

所以,被拍攝的事件的圖像,當它們作為照片呈現出來時,也就成了文化構建的一部分。它不得不隸屬於某種特殊的社會整體面貌,隸屬於攝影師的生活,甚至是一場爭論,一個語言上的實驗,甚是對宇宙的理解方式,或僅僅成為一本雜誌、一次展覽。

Photographers choose the events they wish to capture, and this choice can be regarded as a form of cultural construction, whether intentional or unintentional. The extent of this spatial construction is vividly reflected in their disregard for the things they choose not to photograph. This process of cultural construction, the interpretation of the events before them at this moment, is precisely such interpretation: intuitive and rapid, determining their choice of moments to capture.

Thus, the images of the events when presented as photographs also become a part of cultural construction. They inevitably belong to a certain special social context, to the photographer’s life, or even become a subject of debate, a linguistic experiment, an approach to understanding the universe, or merely part of a magazine or an exhibition.

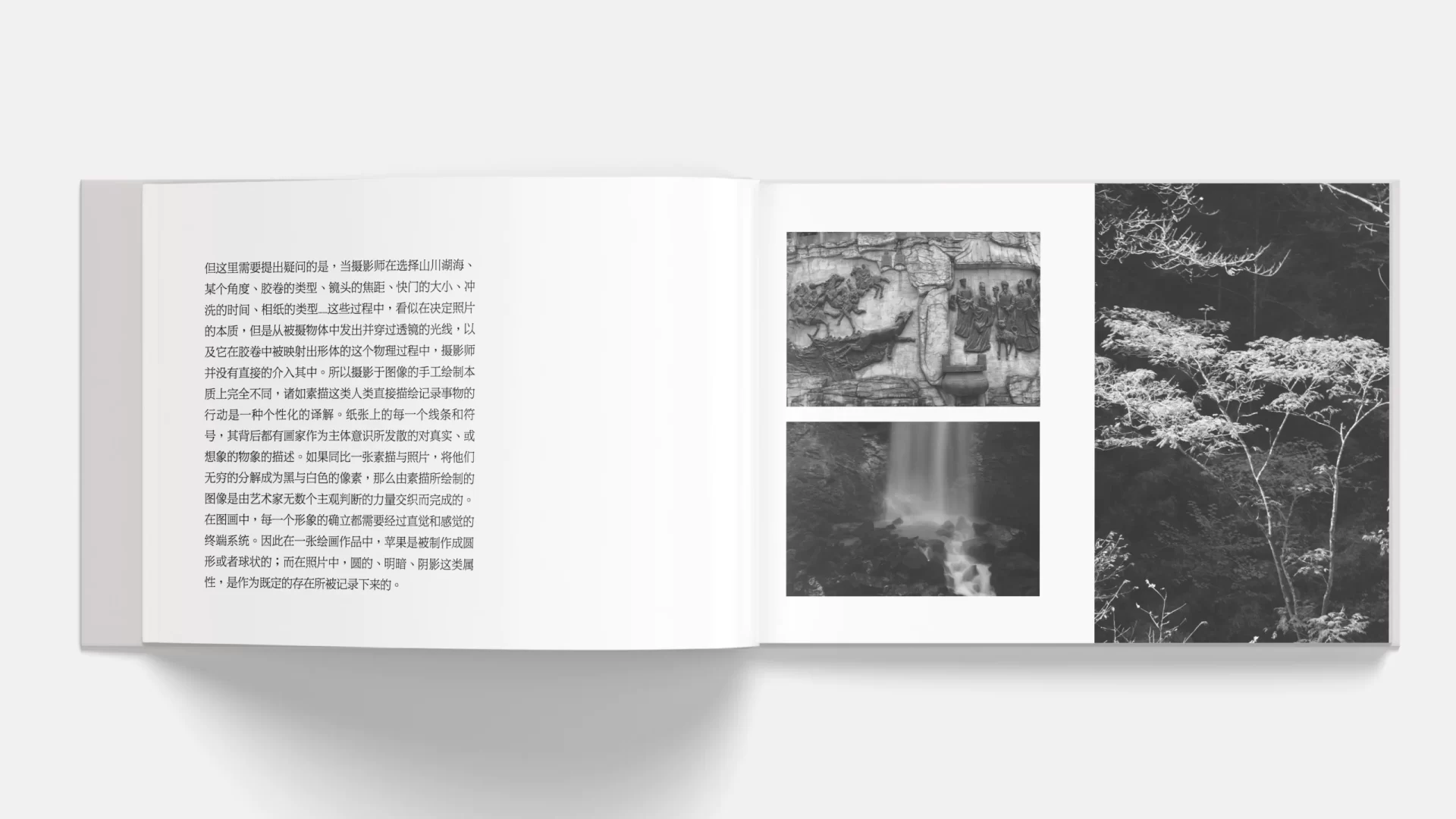

但這裡需要提出疑問的是,當攝影師在選擇山川湖海、某個角度、膠卷的類型、鏡頭的焦距、快門的大小、沖洗的時間、相紙的類型……這些過程中,看似在決定照片的本質,但是從被攝物體中發出並穿過透鏡的光線,以及它在膠卷中被映射出形體的這個物理過程中,攝影師並沒有直接的介入其中。所以攝影於圖像的手工繪制本質上完全不同,諸如素描這類人類直接描繪記錄事物的行動是一種個性化的譯解。紙張上的每一個線條和符號,其背後都有畫家作為主體意識所發散的對真實、或想象的物象的描述。如果同比一張素描與照片,將他們無窮的分解成為黑與白色的像素,那麼由素描所繪制的圖像是由藝術家無數個主觀判斷的力量交織而完成的。在圖畫中,每一個形象的確立都需要經過直覺和感覺的終端系統。因此在一張繪畫作品中,蘋果是被製作成圓形或者球狀的;而在照片中,圓的、明暗、陰影這類屬性,是作為既定的存在所被記錄下來的。

However, a question arises when photographers choose landscapes, a specific angle, type of film, focal length of the lens, aperture size, developing time, type of photographic paper… These steps seem to determine the essence of the photograph, but in the physical process where the light emitted from the subject passes through the lens and is projected onto the film, the photographer does not directly intervene. Therefore, photography is fundamentally different from manual image creation, such as drawing, where humans directly depict and record objects in a personalized interpretation. Every line and symbol on the paper has behind it the subjective consciousness of the artist reflecting on reality or imagined objects. If comparing a sketch to a photograph, breaking them down into infinite black and white pixels, the image drawn by the artist is completed through countless subjective judgments. In a drawing, every figure’s establishment requires an intuitive and sensory terminal system. Hence, in a drawing, an apple is made to appear round or spherical; in a photograph, attributes like roundness, light and dark, and shadows are recorded as given existences.

Therefore, painting and photography are two fundamentally different modes of communication. The numerous judgments and decisions that constitute a painting are based on the artist’s subjective understanding of painting and technique. Thus, these judgments are undeniably systematic, containing a system that becomes a predetermined language, a language that interacts with the objective world. However, within painting, there are different schools, ideologies, and styles, but these are merely various parallel syntactic structures.

Thus, photography should not possess a language of its own. The images in photography are generated through a uniform chemical reaction to exposure; their form and scale are not born out of individual experience or the implantation of meaning. Hence, it is non-systematic, only providing information without having its own language.

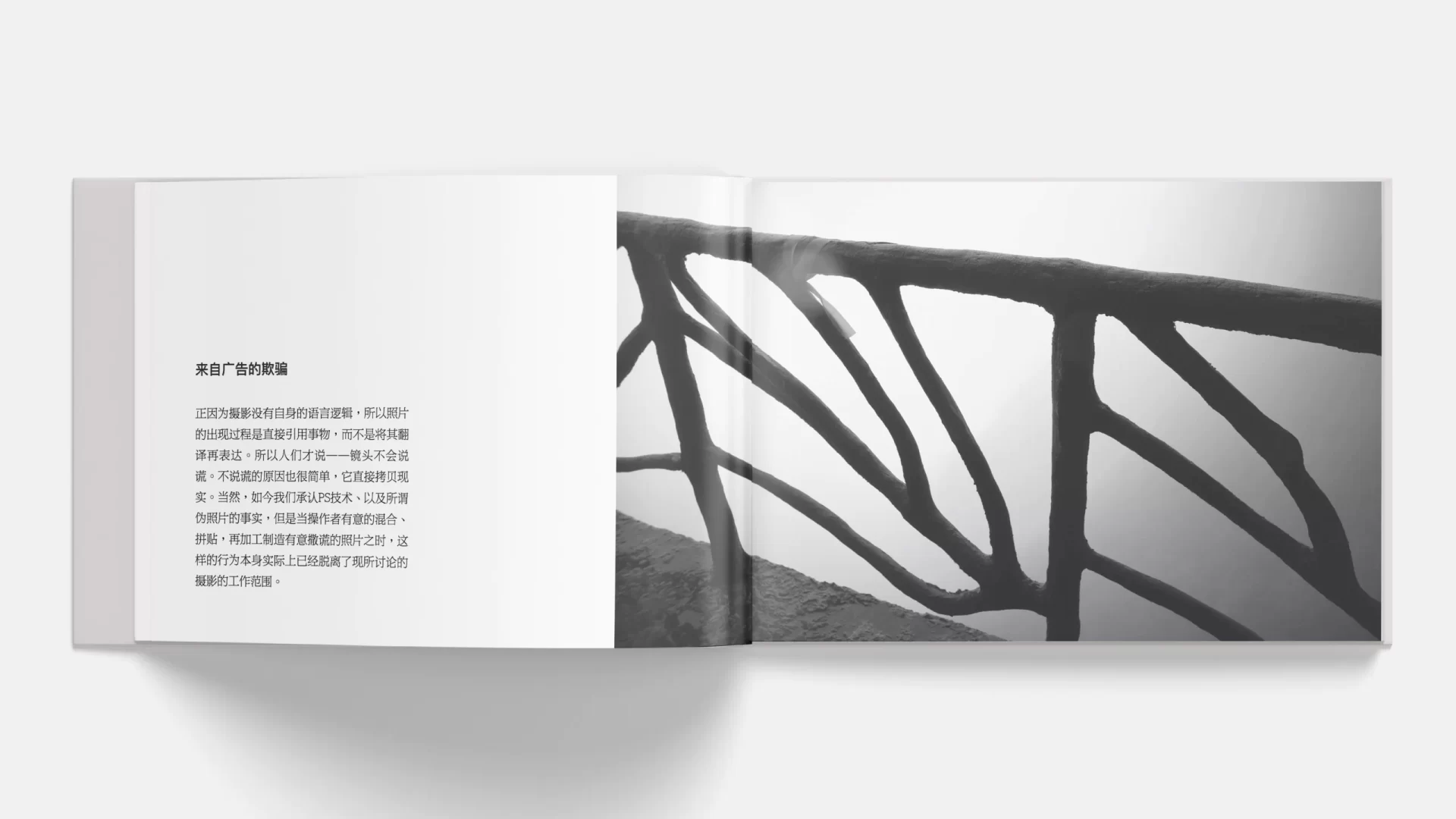

Deception from Advertising

Because photography lacks its own language logic, the appearance of a photo directly references the subject rather than translating and then expressing it. Hence, it is said— the lens does not lie. The reason for not lying is simple; it directly copies reality. Of course, today we acknowledge the existence of Photoshop techniques and so-called fake photos, but when operators intentionally mix, collage, and process to manufacture deceitfully, such actions have actually departed from the realm of photography as discussed.

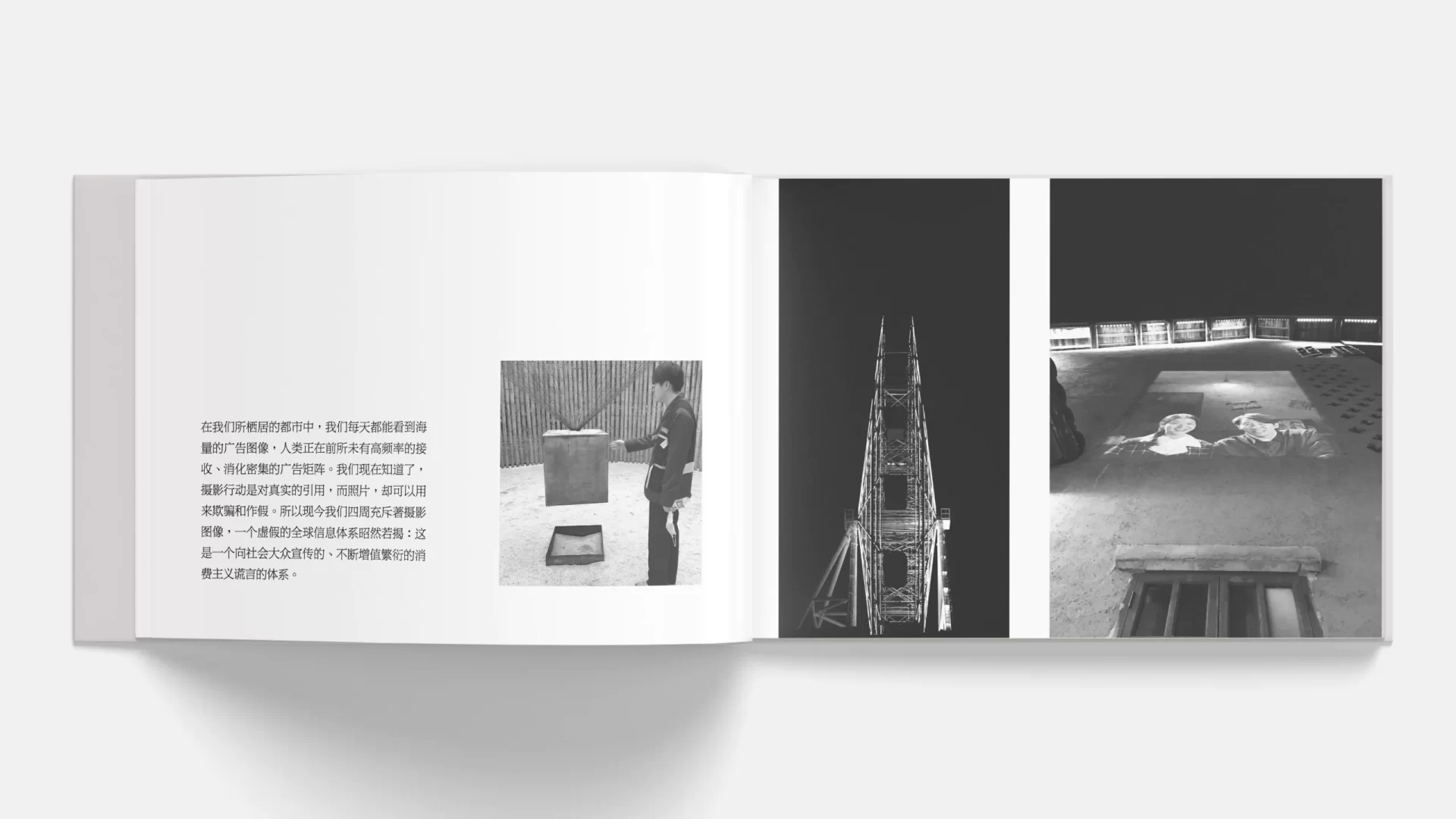

在我們所棲居的都市中,我們每天都能看到海量的廣告圖像,人類正在前所未有高頻率的接收、消化密集的廣告矩陣。我們現在知道了,攝影行動是對真實的引用,而照片,卻可以用來欺騙和作假。所以現今我們四周充斥著攝影圖像,一個虛假的全球信息體系昭然若揭:這是一個向社會大眾宣傳的、不斷增值繁衍的消費主義謊言的體系。

In the urban environments we inhabit, we are exposed daily to an overwhelming amount of advertising imagery, with humans receiving and digesting a dense advertising matrix at an unprecedented frequency. We now understand that photographic action references reality, yet photographs can be used to deceive and falsify. Therefore, our surroundings are flooded with photographic images, revealing a false global information system: a system of consumerist lies that is propagated to the public and proliferates in value.

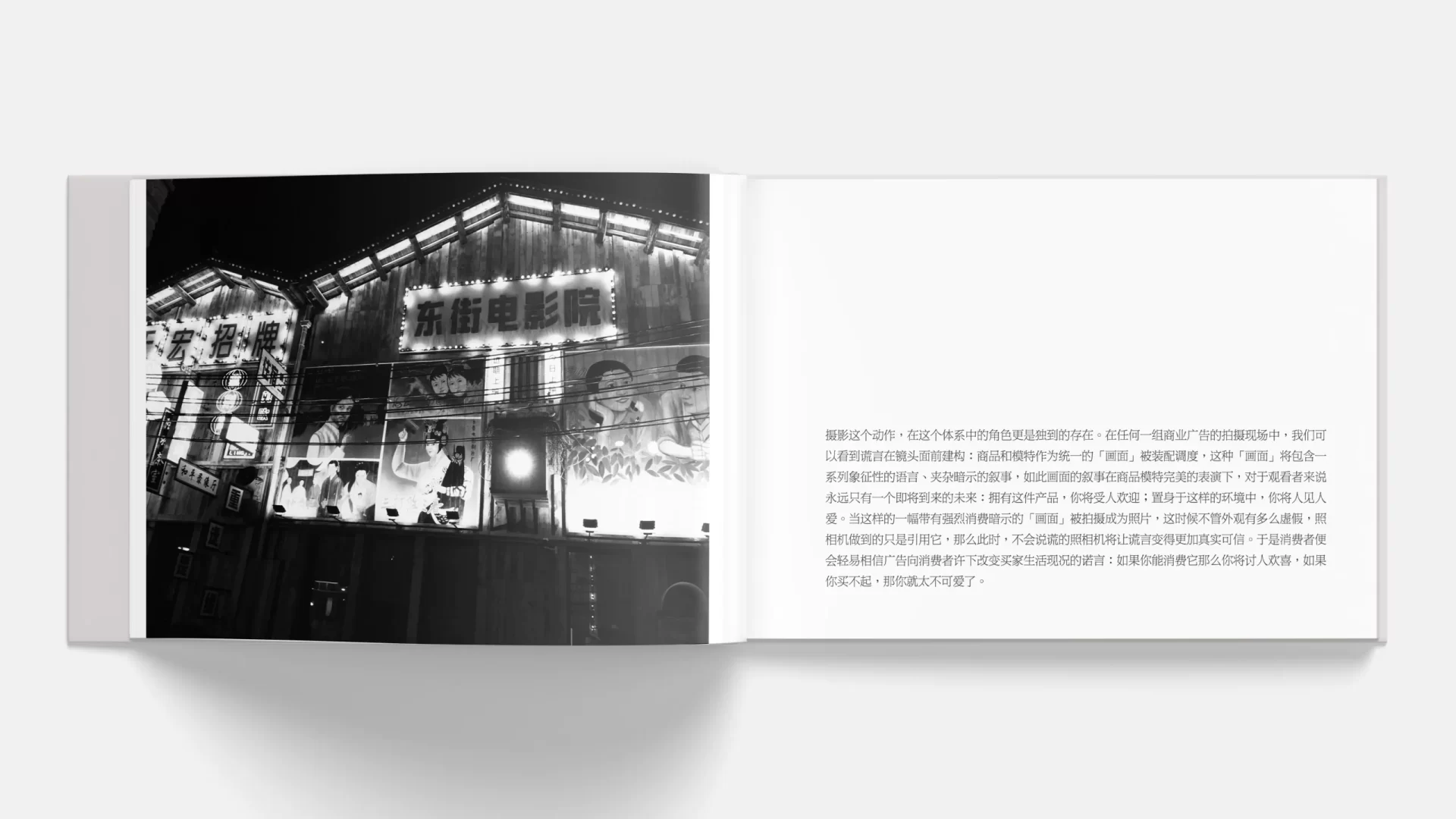

攝影這個動作,在這個體系中的角色更是獨到的存在。在任何一組商業廣告的拍攝現場中,我們可以看到謊言在鏡頭面前建構:商品和模特作為統一的「畫面」被裝配調度,這種「畫面」將包含一系列象徵性的語言、夾雜暗示的敘事,如此畫面的敘事在商品模特完美的表演下,對於觀看者來說永遠只有一個即將到來的未來:擁有這件產品,你將受人歡迎;置身於這樣的環境中,你將人見人愛。當這樣的一幅帶有強烈消費暗示的「畫面」被拍攝成為照片,這時候不管外觀有多麼虛假,照相機做到的只是引用它,那麼此時,不會說謊的照相機將讓謊言變得更加真實可信。於是消費者便會輕易相信廣告向消費者許下改變買家生活現況的諾言:如果你能消費它那麼你將討人歡喜,如果你買不起,那你就太不可愛了。

The act of photography plays a unique role in this system. At any commercial advertising shoot, we can observe lies being constructed in front of the lens: products and models assembled and orchestrated as a unified “image,” which will include a series of symbolic languages and implied narratives. Such narrative frames, under the perfect performance of product models, always suggest one imminent future to the viewers: possessing this product will make you popular; being in such an environment will make you universally adored. When such a strongly suggestive “image” is photographed, no matter how false its appearance, the camera does only refer to it, making the lies seem even more credible. Consequently, consumers are easily convinced by advertisements that promise to change their life’s status: if you can afford it, you will be liked; if you can’t, you are simply not lovable.

參考\摘錄文獻

·黃文.步步為影: 數字化語境中圖像傳播 [M].中國文聯出版社.2008

·約翰·伯格.觀看之道 [M].廣西師範大學出版社.2015

·約翰·伯格.另一種講述的方式:一個可能的攝影理論 [M].中國美術學院出版社.2018

·瓦爾特·本雅明.迎向靈光消逝的年代 [M].廣西師範大學出版社.2008

·顧錚.現代性的第六章面孔[M].上海人民出版社.2007

·克里斯蒂安·科若勒.特定的情境一攝影文化散論[M].北京:作家出版社.2011

·馮克利.當歷史可以觀看[M].廣西師範大學出版社.2013

·孫慨.攝影九章[M].中國攝影出版社.2015

·茨維坦·托多洛夫.個體在藝術中的誕生[M].中國人民大學出版社.2007

·鮑宗豪.數字化與人文精神.[M].上海三聯書店.2003

Reference/Excerpted Literature

Huang Wen. Step by Step into Shadow: Image Communication in a Digital Context [M]. China Federation of Literary and Art Circles Publishing Corporation. 2008

John Berger. Ways of Seeing [M]. Guangxi Normal University Press. 2015

John Berger. Another Way of Telling: A Possible Theory of Photography [M]. China Academy of Art Press. 2018

Walter Benjamin. Towards the Age of Lessening Aura [M]. Guangxi Normal University Press. 2008

Gu Zheng. The Sixth Face of Modernity [M]. Shanghai People’s Publishing House. 2007

Christian Metz. Specific Situations: A Dispersed Essay on Photographic Culture [M]. Beijing: Writers Publishing House. 2011

Feng Keli. When History Can Be Watched [M]. Guangxi Normal University Press. 2013

Sun Kai. Nine Chapters on Photography [M]. China Photography Publishing House. 2015

Tzvetan Todorov. The Birth of the Individual in Art [M]. China Renmin University Press. 2007

Bao Zonghao. Digitalization and the Human Spirit [M]. Shanghai Joint Publishing. 2003